All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Age-related Macular Degeneration (AMD): A Review on its Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Abstract

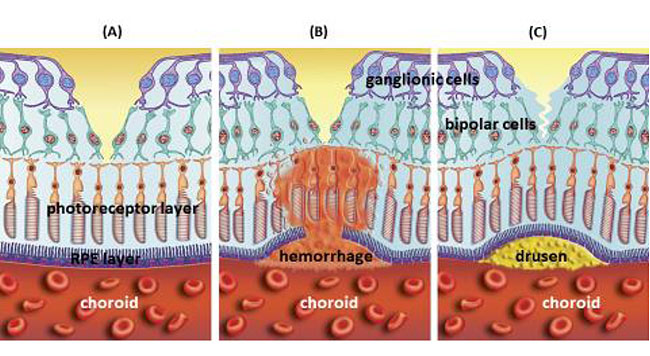

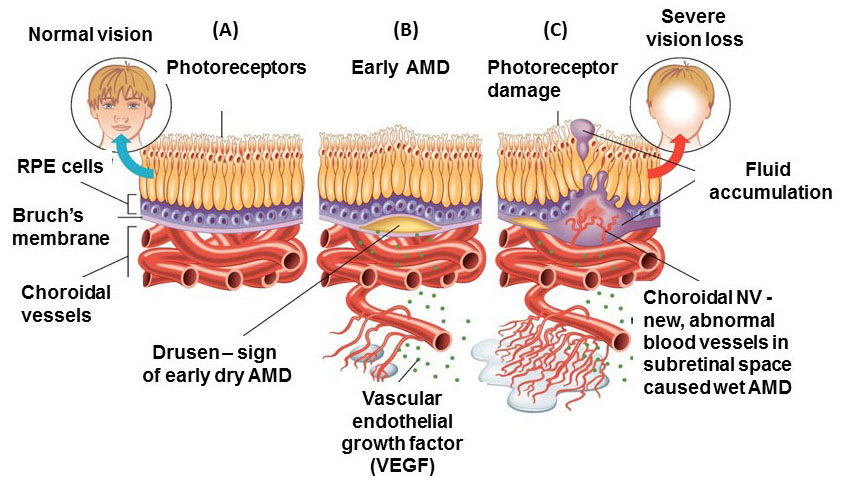

Age-related Macular Degeneration (AMD) is a type of maculopathy that results in irreversible visual impairment among the aged population in developed countries. The early stages of AMD can be diagnosed by the presence of drusen beneath the retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells. The advanced stages of AMD are geographical atrophy (dry type) and neovascular AMD (wet type), which lead to progressive and severe vision loss. The advanced stage of dry AMD can be identified by extensive large drusen, detachment of the RPE layer and finally degeneration of photoreceptors leading to central vision loss. The late stage of wet AMD is diagnosed by the presence of Choroidal Neovascularization (CNV) identified by Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) or retinal angiography. The principal of AMD management is to impede the progression of early AMD to advanced levels. Patients with CNV are treated with anti-VEGF (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor) compounds to inhibit blood vessel growth and thereby reducing vision loss. Although preventive methods for dry AMD are under investigation, there are no proven effective treatments.

A variety of environmental and genetic related risk factors are associated with increased incidence and progression of AMD. The genetic factors are found in the complement, angiogenic and lipid pathways. However, environmental factors, such as smoking and nutrition, are also major risk factors. Smoking is a modifiable environmental risk factor, which greatly increases the incidence and progress of AMD compared to non-smokers. There is growing evidence for the positive influence of a healthy diet containing high levels of anti-oxidant supplements. The reduction of serum lipids is another effective strategy for prevention AMD. Although no single preventive approach has been identified, knowing the high risk factors of AMD, along with modification of lifestyle is important for this multifactorial disease, especially in populations with higher genetic susceptibility. Though recent progress in early diagnosis of the disease has facilitated early and efficient intervention, further studies are required to gain more clarification of specific pathophysiology.

In spite of decades of focused research on AMD, the pathogenesis of AMD is still not completely understood. Recently, numerous novel methods, including imaging techniques, new drug delivery routes, and therapeutic strategies, are improving the management of AMD. In this review, we discuss the current knowledge related to epidemiology and classifications of AMD.

1. INTRODUCTION: DEFINITION, EPIDEMIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS

1.1. Definition

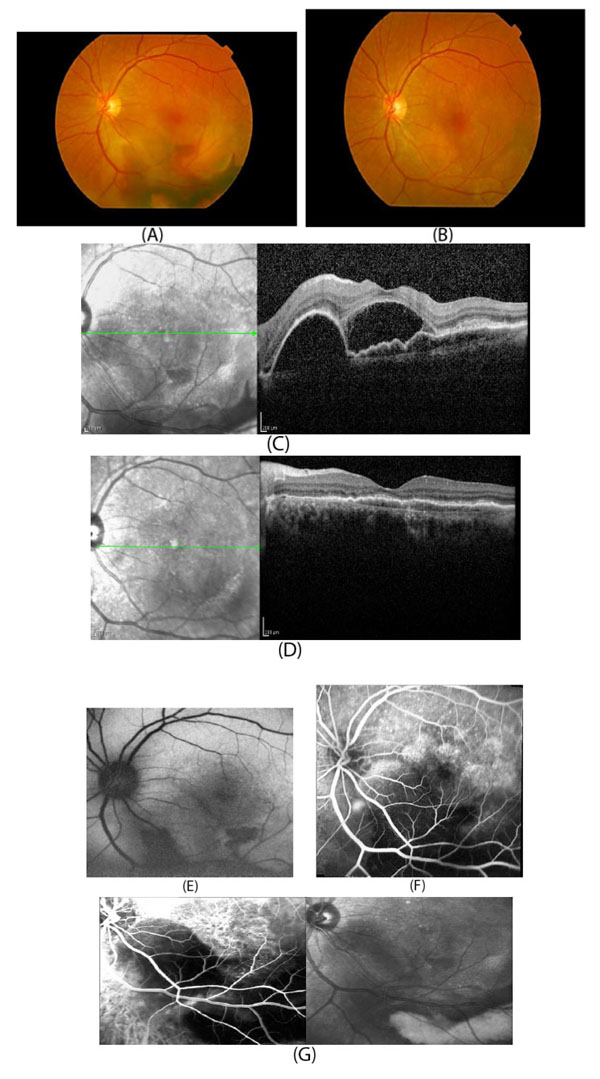

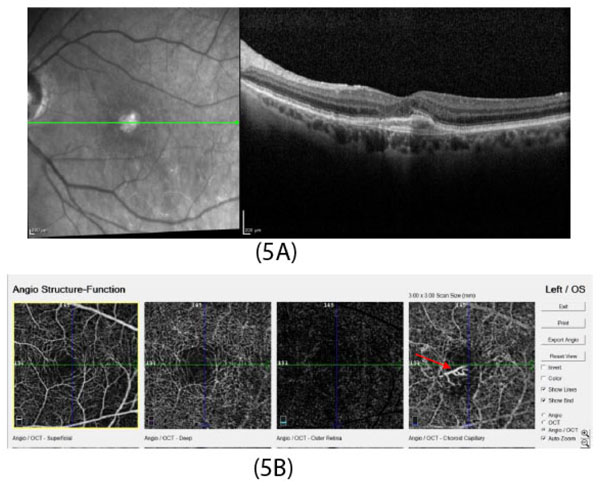

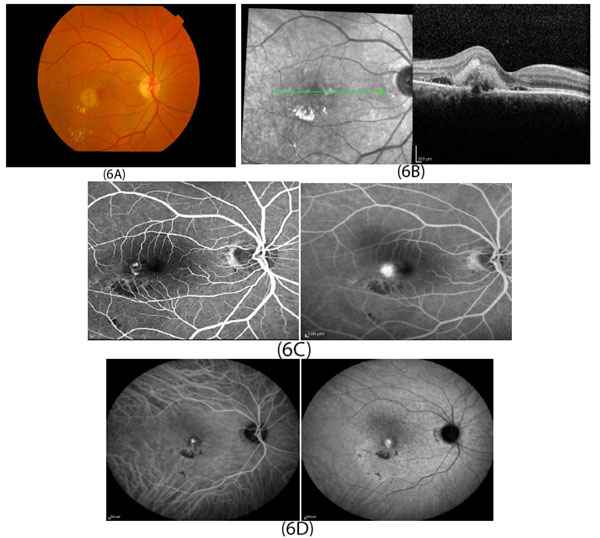

In developed countries, large proportions of the elderly population suffer from severe visual difficulties resulting from AMD and this trend is rising worldwide because of the growing number of older individuals [1]. Based on a previous study, more than 1.75 million people in the United States are affected by AMD and it is estimated to reach almost 3 million by 2020 [2]. The early stages of AMD are identified by the presence of hallmarks known as drusen and depigmentation of the RPE cells. Various types of drusen are associated with different levels of risk for AMD (Table 1). AMD progression from early to intermediate and advanced level is due to increased numbers of drusen and degeneration of RPE cells leading to pigmentary changes and formation of abnormal new blood vessels, respectively (Table 2) [3, 4]. The different stages of AMD during disease progression from early to advanced levels are illustrated in Figs. (1-3). The advanced levels of AMD are categorized into two forms: non-neovascular (dry, non-exudative or geographical) and neovascular (wet or exudative) AMD (Table 2) [4]. In dry AMD, geographic atrophy occurs in the RPE, photoreceptors and choriocapillaris, causing diminished visual acuity as a consequence of gradual cellular loss. In wet-type AMD, choroidal neovascularization leads to subretinal leakage of blood, lipids, fluids, and formation of fibrous scars [5-10]. Three types of CNV can be differentiated in wet type AMD. Type 1 CNV, also known as occult CNV, is located in sub-RPE space (Fig. 4A-4G) and type 2 CNV, known as classic CNV, is located in sub-retinal space (Fig. 5A). Additionally, type 3 CNV is identified as a proliferation of intraretinal angiomatose [11] (Figs. 6A-6D). There are a variety of imaging techniques available for guiding physicians facilitating the diagnosis and evaluation of response to therapy in patients with AMD. The useful imaging techniques in this regard include Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT), Fluorescein Angiography (FA), fundus photography, Indocyanine Green Angiography (ICG) and fundus autofluorescence imaging. The selection of the imaging technique depends on the patients’ clinical status [12]. Examples of multimodal imaging of different types of CNV in patients with exudative AMD are shown in Figs. (1-3). In spite of significant advancements associated with diagnostic and treatment methods of AMD, further investigations are needed to identify effective therapies for dry forms of AMD and reduce the injection frequency of anti-VEGF compounds for wet AMD.

1.2. Epidemiology

In recent decades, numerous studies have been conducted on the epidemiology of AMD. Congdon et al. have estimated that 54% of the older white population that was legally blind in the United States suffered from AMD [13]. In 2003, approximately 8 million individuals ages 55 or beyond were affected by intermediate or the late forms of AMD in the United States [14]. Similarly, in the United Kingdom, the visual loss of approximately 75% of persons over 85 years was attributed to AMD [15]. Epidemiological surveys among populations with diverse ethnicities represent varied prevalence of AMD. Friedman et al. demonstrated that while drusen have frequent incidence in both white and black elderly populations, whites are remarkably more susceptible to develop advanced AMD [16]. When comparing Asian and Caucasians individuals affected with wet AMD, Asians are much more likely to have Polypoidal Choroid Vasculopathy (PCV), a modified form of AMD compared to Caucasian patients [17]. Klein et al. estimated that in the United States, the incidence of AMD in the elderly will rise significantly from 8% in 2005 to 54% in 2025 [1]. In this study, among participants between 43-54 years, the estimated rates for early and late AMD were 14.3% and 3.1%, respectively. However, the incidence rate of severe AMD reached 8% for persons over 75 years of age, making it a major problem affecting public health [1]. During a five-year study in Australia, the incidences of early AMD among people younger than 60 years and more than 80 years were estimated to be 13% and 20%, respectively [18]. Smith and colleagues investigated three groups of racially identical participants from Australia, North America, and Europe. While AMD was seen in only a small proportion (0.2%) of people between 55-64 years of age, its prevalence increased to more than 13% of individuals over 85 years, without significant gender differences [19].

| Different types of drusen | Sizes | Edges | Shape | Location | Risks related to AMD | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soft | Large (>125 |

Distinct or indistinct edge | Dome-shaped | Central retina | Increases the risk of severe AMD and RPE pigmentation | [84, 85] |

| Hard | Small (<63 |

Distinct edge | Round | Throughout the retina | Increases risk of presentation of soft drusen | [86] |

| Cuticular drusen | Small (25-75 |

Uniformly sized, “stars in the sky” pattern | Triangular, saw tooth | Around fovea | Increases the risk of CNV | [86-88] |

| Reticular pseudodrusen | Large (100-250 |

Irregular borders |

Networks of oval or round lesions | Located on apical surface of RPE | Increases the risk of advanced forms of AMD | [89-92] |

| Stage of AMD | Number and size of drusen | Other abnormalities | Management | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Normal aging | No drusen or signs of few small (<63 µm) sized drusen in one/both eyes, or medium sized drusen in one eye | No signs of pigmentation | |

| 2 | Early AMD | Presence of few medium (63-125 µm) sized drusen in one or both eyes | Pigmentation | Modification of diet and lifestyle |

| 3 | Intermediate | Extensive medium drusen in both eyes or at least one large drusen in one eye | Geographical atrophy without macular involvement | |

| 4 | Advanced dry AMD | Large drusen (>125 µm) drusen or extensive medium in both eyes | Geographical atrophy extending to macula | Lifestyle management, Anti-oxidant supplements |

| 5 | Advanced neovascular AMD | Extensive large drusen in the fovea in both eyes besides hemorrhage and scars | CNV, fluid leakage, RPE detachment, Visual acuity less than 20/32 | Anti-VEGF therapy, laser therapy |

1.3. Risk Factors

Aging is the most consistent non-modifiable environmental risk factors for AMD [20, 21]. Besides aging, ethnicity and gender are also significant non-modifiable risk factors. There are no significant differences in frequencies of drusen between white and non-white populations. However, it has been showed that white female individuals are more susceptible to develop severe, late forms of AMD compared to black individuals [19, 22-24]. Smoking, higher body mass index, cardiovascular disease, high fat diet with restricted anti-oxidant compounds (e.g. vitamin A, vitamin C, vitamin E and zinc oxide) and unhealthy lifestyle are environmental risk factors associated with AMD [25-28].

Previous studies have shown that smoking, especially among women, significantly impacts the progression of AMD. The threat is the highest among active smokers but passive smokers are also affected negatively [19, 29-31]. The exact mechanism by which smoking impacts AMD is not clear. Some studies have shown that smoking causes a decline in serum antioxidant levels, potentially affecting the macula, which is highly sensitive to oxidative stress [32, 33]. Moreover, other studies have validated smoking as a critical oxidative stressor that promotes the occurrence of AMD. The authors suggest that as a result of the oxidative stress generated by smoking, the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) become damaged, which induces RPE degradation and contributes to the formation of drusen [34-36]. In addition, smoking enhances atherosclerosis susceptibility that induces damage to choroidal vessels [37, 38]. Cardiovascular disease risk factors, such as hypertension and high serum cholesterol levels, are also associated with AMD [39-41]. Individuals with AMD are more predisposed to a range of cardiovascular diseases, including myocardial infarction [41, 42]. Previous studies emphasized for AMD patients the beneficial role of a healthy diet containing a larger proportion of fruits, vegetables and fish oil in contrast to diets of red meat, carbohydrates, oily and processed foods [43]. Husain et al. studied the association between AMD and serum lipid profile among 300 patients aged 50 years and beyond. The authors reported that the majority of 150 cases (82.66%) had some form of dry AMD as compared to the 17.33% of cases with wet type AMD. Therefore, it was suggested that the serum lipid profile, particularly triglycerides (TG) and Very Low Density Lipoprotein (VLDL) are associated with increased risk of AMD [44]. Other studies have shown that due to limited production of estrogen during early menopause, females can be at greater risk to develop AMD [45, 46]. In this regard, Snow and colleagues reported positive outcomes from exogenous estrogen therapy to diminish the risk of advanced AMD in post-menopausal patients [47].

Twin and familial aggregation/segregation studies have revealed that family history can be a risk factor in AMD [48-50]. There is a statistically higher concordance of AMD in monozygotic twins compared to dizygotic twins [51]. The risk of late AMD in siblings of parents with advanced AMD is approximately 4-fold higher compared to intermediate AMD. Also, first-degree relatives of those suffering from advanced AMD are more susceptible to developing Age-related Maculopathy (ARM) and may show earlier manifestations of AMD [52].

Several chromosomal loci associated with AMD have been identified. There are two major genetic regions contributing to AMD. The first identified susceptible gene for AMD was complement factor H (CFH), located on chromosome 1q31.3. The second major gene was LOC387715/HTRA1 located on 10q26 chromosome, which encodes a serine protease [53, 54]. Recently, Corominas and colleagues conducted a Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) study on 1361 control individuals and 1125 participants with AMD, which had European ancestry. Authors have identified that COL8A1 (collagen type VIII alpha 1 chain) gene located on 3q12.1 chromosome is a component of Bruch’s membrane, which is damaged in AMD. They revealed that in control participants, there were fewer alterations in that gene (0.4%) compared to AMD patients (1.0%). Therefore, it was suggested that the alteration of Bruch’s membrane integrity by the COL8A1 gene contributes to the formation of drusen thereby playing a role in AMD development [55]. Additional genetic risk factors are Angiotensin-converting Enzyme (ACE), apolipoprotein E (APOE) and ATP-binding cassette rim (ABCA4) [56]. Allikmets et al. reported that changing the amino acids D2177N and G1961E on the ABCR (ABCA4) gene also has a significant association with AMD [57].

The APOE gene, a major regulator of lipids metabolism, is located on chromosome 19q13.2 [58]. Among three major alleles of APOE, the epsilon 2 allele of APOE gene has been shown to be a higher risk for AMD [59], whereas, APOE epsilon 4 allele has a protective effect for AMD [60, 61]. Also, ACE (located on chromosome 17q23) with its Alu +/+ genotype has a protective role against AMD [62]. Other studies have demonstrated that the upregulation of C2, C3, CBF, CFI genes in the complement pathway are negative influential factors for AMD [63-67].

There are also genes within specific biological pathways associated with AMD. For example, overexpression of genes encoding angiogenesis (VEGFA), extracellular collagen matrix (FRK/COL10A1), serum HDL (LIPC and CETP), and immune pathways (e.g. CFH, CFB and C3) are negatively associated with early AMD and its progression to the advanced stage [63-65, 68-70]. Substantial distinctions of the dominance of risk alleles between geographical and neovascular AMD have not been demonstrated [71].

Recently, epigenetic modification of genes has gained considerable attention for associations with AMD. Stable epigenetic markers may be a link between environmental exposure and genetic alterations in AMD [72-76]. The epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation, acetylation and histones alterations may have protective or detrimental roles in AMD [77-81]. Udar and colleagues have reported specific single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) variants in mitochondrial (mt) DNA of AMD patients compared to normal subjects and an increased association between AMD and individuals with the U, T and J mtDNA haplogroups [82]. Also, in Austria, Mueller and colleagues analyzed mitochondrial haplogroups of 66 patients with dry AMD, 385 control participants and 200 persons suffering from exudative AMD. They reported that although haplogroup J was remarkably frequent in patients with neovascular AMD, the frequency of haplogroup H was considerably less in wet AMD subjects, demonstrating that the haplogroup H mtDNA has a protective role against AMD [83].

Future therapies for AMD may target genetic and epigenetic variations but additional studies are required to acquire full understanding at a molecular level how they are related to AMD pathogenesis.

OCT angiography image (Fig. 5A) shows type 2 CNV in choroidal capillary layer (red arrow).

CONCLUSION

Age-related macular degeneration negatively affects visual acuity in the elderly population. Although there is no single preventive method, alteration of modifiable risk factors can effectively impede the development of AMD. Both genetic and environmental risk factors are influential in the occurrence of AMD. Several major gene loci have been demonstrated as profoundly affecting the development of AMD. Modification of environmental risk factors, such as smoking and diet can play a preventive role in the progression of AMD. Recent progress in early diagnosis of the disease has facilitated early and efficient intervention. Anti-VEGF drugs have been influential agents for inhibition of CNV leading to the improvement of visual acuity. Nevertheless, these anti-VEGF agents have a high burden on patients because monthly injections are often required over extended periods of time. Fortunately, other new therapeutic approaches are being investigated, such as regenerative treatment options, which might yield better outcomes in the future. Further studies are required to gain more clarification of specific pathophysiology mechanisms that will allow us to develop novel preventive and therapeutic pathways in the future.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

FUNDING

Discovery Eye Foundation, Polly and Michael Smith, Edith and Roy Carver, Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Foundation, Unrestricted Departmental Grant from Research to Prevent Blindness and NEI R01 EY0127363 (MCK), Arnold and Mable Beckman Foundation and support of the Institute for Clinical and Transnational Science (ICTS) at University of California Irvine.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.