All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Spontaneous Suprachoroidal Hemorrhage in a Patient on Apixaban: A Case Report

Abstract

Introduction

We, herein, present a rare case report evaluating an elderly patient who developed spontaneous suprachoroidal hemorrhage (SSCH) while using apixaban (direct oral anticoagulant agent).

Case Presentation

An 82-year-old man with a known history of hypertension and atrial fibrillation on apixaban presented with a sudden onset of flashes, floaters, and a temporal curtain-like visual field defect in his right eye. He had no preceding history of trauma or recent ocular surgery. Ophthalmological examination revealed two large elevated grayish choroidal lesions with associated exudative retinal detachment. Ultrasonography and wide-field fluorescein angiography confirmed the diagnosis of SSCH. The patient was managed with topical steroids and cyclopentolate. One month later, the vision improved, and the hemorrhage showed signs of resolution.

Discussion

Direct oral anticoagulant agents (DOACs) are safer and carry a lower risk of major bleeding events compared to the traditionally used antiplatelet therapy and thrombolytic agents; however, patients may still be at risk of spontaneous suprachoroidal hemorrhage.

Conclusion

Spontaneous suprachoroidal hemorrhage can very rarely occur with the use of DOACs, with only two cases reported in the literature, and here, we present a case of SSCH in a patient while using apixaban.

1. INTRODUCTION

Suprachoroidal hemorrhage (SCH) is a fulminatory accumulation of blood within the suprachoroidal space [1]. It is considered an uncommon, serious complication, and is usually associated with ocular surgery or trauma [2, 3]. Patients who develop this condition usually present with an acute and sudden decrease in vision, acute angle closure glaucoma, and have a poor visual prognosis [3]. Although SCH can occur spontaneously, it is considered a very rare occurrence [4]. Ocular risk factors that have been associated with suprachoroidal hemorrhage include age-related macular degeneration, glaucoma, high myopia, and aphakia [5]. Spontaneous suprachoroidal hemorrhage has been reported mainly with older anticoagulants (e.g., warfarin, low-molecular-weight heparin), antiplatelet agents, or thrombolytics [1, 2, 3]. Newer DOACs, such as apixaban, are known to carry a better safety profile and significantly lower risk of bleeding compared to the aforementioned agents [6, 7, 8]. However, we have, herein, reported a case of SSCH associated with the direct oral anticoagulant agent apixaban. Of note, the hemorrhage was localized and limited, simulating the clinical appearance of choroidal melanoma.

2. CASE REPORT

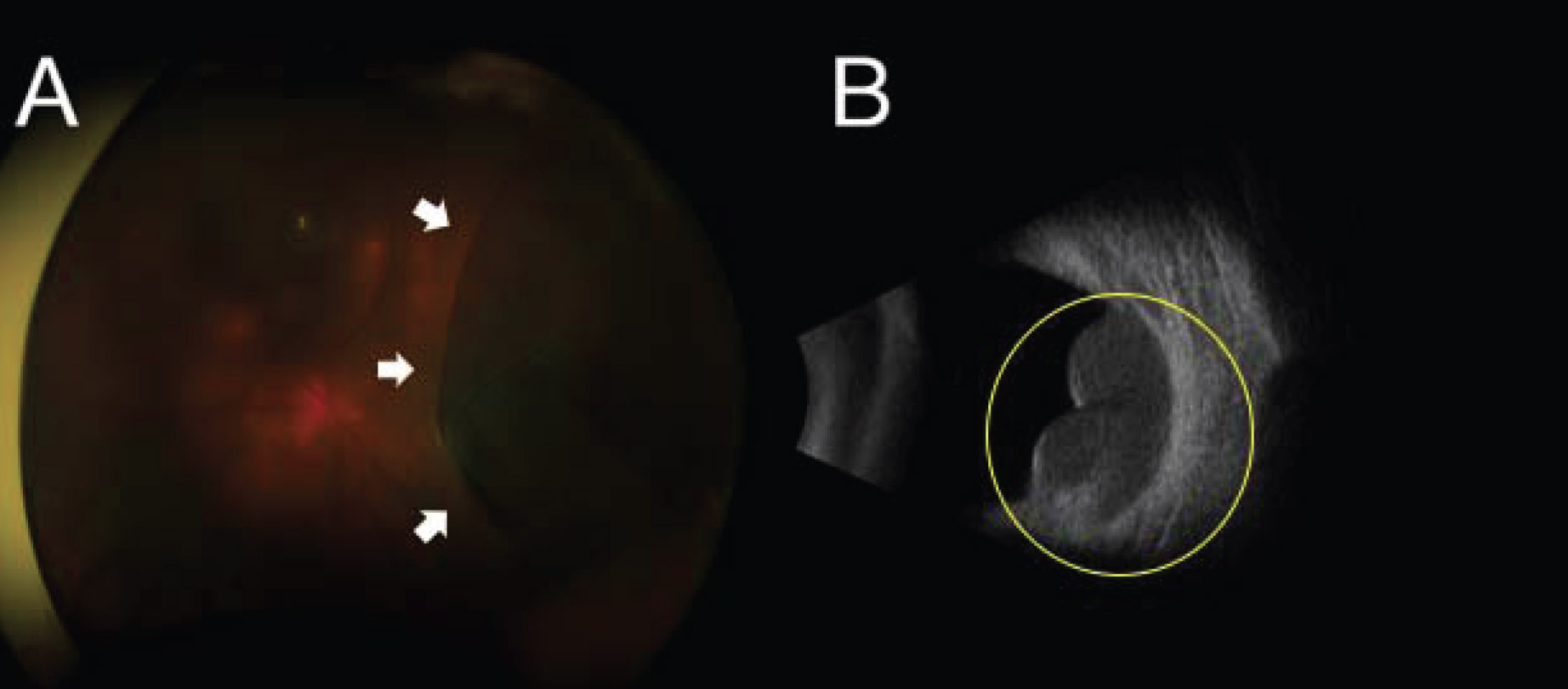

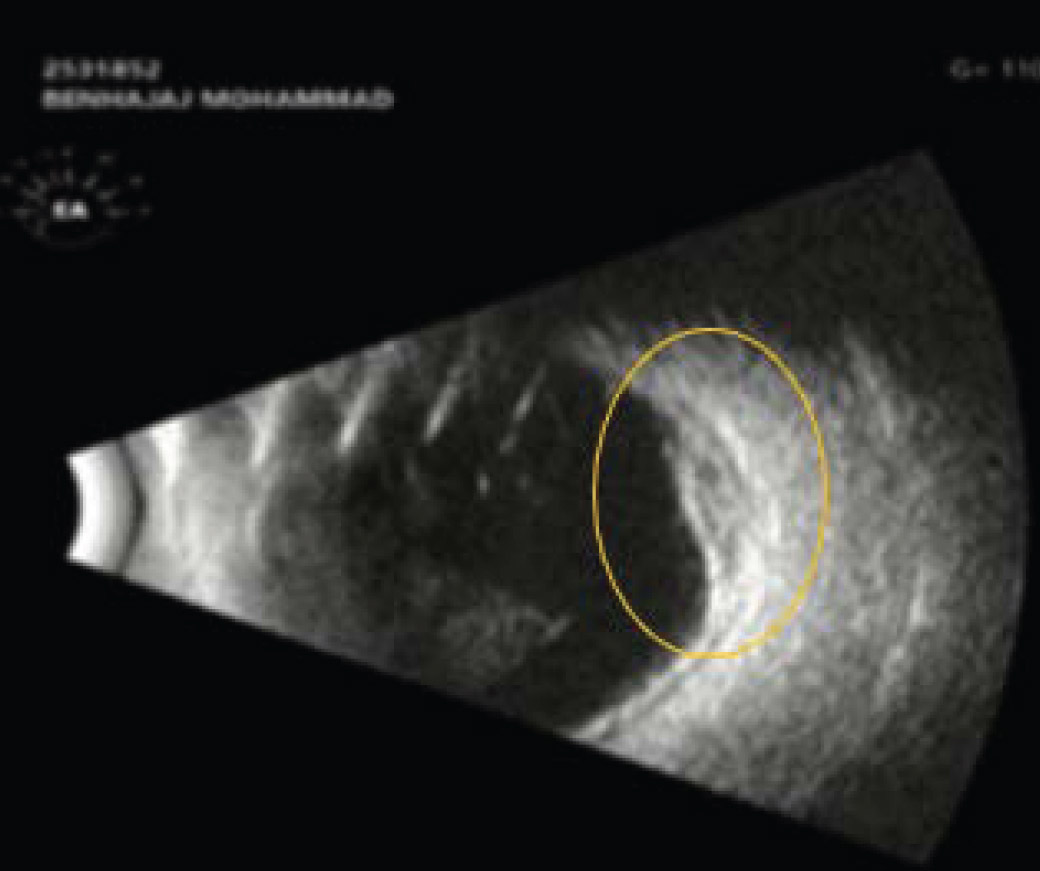

An 82-year-old man presented to the emergency room complaining of a sudden onset of flashes, floaters, and a temporal visual field defect in the right eye that started one day before presentation. The patient denied any recent history of eye surgery or trauma. His past medical history was positive for hypertension, chronic atrial fibrillation (on apixaban anticoagulant), and a cerebral vascular accident. His past ophthalmic history was positive for cataract surgery in both eyes, performed 20 years back, and a successful penetrating keratoplasty in the right eye, performed 2 years back, for a corneal scar due to trachoma. Ophthalmological examination of the right eye showed a visual acuity of 20/400, a clear sutureless corneal graft, a deep and quiet anterior chamber, and an intraocular pressure (IOP) of 10 mmHg. Fundoscopy of the right eye revealed two grayish choroidal lesions, a larger one localized nasally and a smaller one superotemporally, both of which were associated with subretinal fluid (Fig. 1A). An examination of the left eye demonstrated a visual acuity of 20/200, Herbert pits with a corneal scar, and an otherwise unremarkable anterior segment and fundus examination. Ocular posterior segment ultrasonography (US) examination of the right eye was consistent with findings suggestive of bullous hemorrhagic choroidal detachments associated with minimal subretinal fluid (Fig. 1B). The patient was managed with close observation and started on topical steroids and cyclopentolate for the right eye. One month later, his vision improved to 20/200 in the right eye, and the SCH showed signs of resolution. Ocular posterior segment ultrasonography (US) of the right eye after 1 month showed a shallow SCH inferonasally with a stable SCH in the superotemporal quadrant of the retina (Fig. 2).

3. DISCUSSION

Several cases of spontaneous suprachoroidal hemorrhage (SSCH) have been reported in the literature [2]. This rare entity has been described mainly in patients on anticoagulants (namely warfarin and low-molecular-weight heparin), antiplatelets (such as aspirin and clopidogrel), and thrombolytic therapy with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) or streptokinase. In the majority of cases in which patients are on anticoagulation/antiplatelet/thrombolytic therapy, another associated risk factor is usually present, such as advanced age, systemic hypertension, atherosclerosis, diabetes mellitus, chronic renal disease, cardiovascular/ cerebrovascular disease, preceding Valsalva maneuvers, and/or age-related macular degeneration, which is the most commonly associated ocular risk factor [9-13].

In this case report, we have described the case of a patient who presented with SSCH while on direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) apixaban. In the literature, there are only two cases of SSCH associated with DOAC medication use, specifically rivaroxaban and dabigatran [9]. Additional risk factors that may have likely contributed to our patient’s spontaneous hemorrhage included old age, systemic hypertension, and cardiovascular disease.

Wide-field colored fundus photograph of the right eye showing large grayish choroidal lesions localized nasally (white arrows) with minimal subretinal fluid (A). Ocular posterior segment ultrasonography (US) examination showed bullous hemorrhagic choroidal detachment along the nasal arcade (circle) with minimal subretinal fluid (B).

Ocular posterior segment ultrasonography (US) examination showed shallow choroidal detachment nasally (circle) and inferiorly, with no subretinal fluid.

Apixaban is an oral drug that works as a direct factor Xa inhibitor, inhibiting both free and clot-bound factor Xa, and has been approved in various thromboembolic conditions, including atrial fibrillation, which was the indication for use in our patient [7]. Over the last decade, direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), such as apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban, have become widely available and are replacing the traditional vitamin K antagonists (VKAs), such as warfarin, in patients at risk of thromboembolic events. This shift in practice occurred after randomized control trials and observational studies confirmed that these newer anticoagulants are both efficacious and safer than the traditionally used VKAs, demonstrating a significantly lower rate of major bleeding events in patients on these medications [6, 7, 8]. However, as more patients have started using these medications, the literature has recently been seeing more reports describing bleeding events in patients on these medications. Apixaban has been reported recently in multiple case reports to be associated with life-threatening spontaneous hemorrhagic pericardial effusion leading to significant morbidity and mortality [14-20]. Thus, it is important for physicians to remain aware that the risk of bleeding with DOACs, though small, is still present.

In our case report, our patient presented with a localized and limited SCH that did not progress. The hemorrhage was resolved without permanent vision loss and/or vision-threatening complications, such as acute angle closure glaucoma. Our patient also did not require any surgical intervention. This is in contrast to the majority of reported cases of SSCH associated with the use of traditional anticoagulant medications, particularly warfarin and low-molecular-weight heparin, antiplatelet therapy, or thrombolytic agents; many of these cases have presented with severe and permanent vision loss due to massive SCHs, sometimes complicated with acute angle closure glaucoma and often requiring surgical intervention [19, 20]. The limited and self-resolving nature of hemorrhage in our patient was consistent with the higher safety profile and lower associated risk of bleeding events associated with DOACs compared to older anticoagulants, antiplatelets, and thrombolytic therapy.

The localized and limited nature of SCH in our patient was confused with the characteristic appearance of choroidal melanoma as well as peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR). A localized, dome-shaped lesion, being gray-brown in color and presenting in a patient of old age complaining of a visual field defect associated with photopsia, raises suspicion for both choroidal melanoma and PEHCR. This confusion has been previously reported in the literature. Three cases were reported by Morgan et al. [21] In a study by Shields et al., a review of over 12,000 patients who were referred to a tertiary referral center as cases of choroidal melanoma demonstrated 2% of pseudo-melanomas to be cases of hemorrhagic choroidal detachment. In the same study, PEHCR was diagnosed in 8% of pseudo-melanoma cases [22]. Fung et al. further reported several cases of SCH referred to a tertiary referral center as cases of choroidal melanoma [23]. Two cases of cough-induced SCH and a case of SSCH in a patient with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura simulating choroidal melanomas have also been reported in the literature [15, 24].

The work-up in our patient was aimed initially at ruling out choroidal melanoma (a life- and vision-threatening condition), followed by PEHCR (a potentially vision-threatening condition sometimes requiring prompt treatment) [25, 26]. Based on multimodal imaging (particularly ultrasonography and wide-field fluorescein angiography), a diagnosis of SCH was confidently made in our patient. B-scan ultrasonography of the lesion showed a localized bullous hemorrhagic choroidal detachment that was hyperechoic, with minimal subretinal fluid, and no choroidal excavation. In contrast, choroidal melanomas demonstrate a generally acoustically hollow lesion on B-scan, may present with a collar button configuration, may be associated with more significant subretinal fluid, and may demonstrate choroidal excavation [24]. PEHCR lesions may appear dome- or plateau-shaped and demonstrate variable echogenity on B-scan, resembling SCH [25, 26]. Therefore, B-scan ultrasonography was followed by wide-field fluorescein angiography, which showed only blockage, no vascularity (ruling out choroidal melanoma), and no hyper- or hypo-fluorescence suggestive of areas of RPE atrophy or hyperplasia [25].

Associated risk factors should be controlled to avoid progressive or recurrent hemorrhage; this may include controlling blood pressure and temporarily stopping or reversing anticoagulation therapy if the patient’s systemic medical condition permits under the care of an internist/ cardiologist/hematologist [2, 3, 4]. In our patient, the hemorrhage resolved with conservative management, observation, and temporary discontinuation of anticoagulation therapy.

CONCLUSION

DOACs, such as apixaban, are a relatively new class of anticoagulants. These medications are safer and carry a lower risk of major bleeding events compared to the traditionally used VKAs, antiplatelet therapy, and thrombolytic agents. Nevertheless, patients may still be at risk of spontaneous bleeding. When bleeding manifests in the eye due to a spontaneous suprachoroidal hemorrhage (SSCH), it may carry a less severe course and present with a distinct clinical picture simulating choroidal melanoma and PEHCR. Therefore, an appropriate work-up with B-scan ultrasonography and fluorescein angiography (FFA) is indicated to rule out these more serious conditions.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: J.A.: Data collection; Y.A., F.A.: Drafting of the manuscript; H.A.: Writing, review, and editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| SCH | = Suprachoroidal hemorrhage |

| SSCH | = Spontaneous suprachoroidal hemorrhage |

| PEHCR | = Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy |

| DOACs | = Direct oral anticoagulants |

| IOP | = Intraocular pressure |

| TPA | = Tissue plasminogen activator |

| VKAs | = Vitamin K antagonists |

| US | = Ultrasonography |

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this article and any accompanying images.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

All the data and supporting information are provided within the article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.