All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Tectonic Keratoplasty in Patients with Non-traumatic, Non-infectious Corneal Perforations

Abstract

Introduction:

The study aims to report clinical results of tectonic keratoplasty for non-traumatic, non-infectious corneal perforations.

Materials and Methods:

The medical records of 12 patients who underwent tectonic penetrating keratoplasty between October 2014 and August 2018 at Ege University Ophthalmology Department were retrospectively reviewed.

Results:

The mean age of the patients was 52.92±30.34 (range, 2-82) years. The causes of corneal perforation were dry eye (neurotrophic keratopathy (n=4), limbal stem cell deficiency (n=2), exposure keratopathy (n=2) and graft versus host disease (n=1)) in 9 patients. In the remaining 3 patients, the etiology of perforation was not determined. The mean Visual Acuity (VA) was 2.98±0.39 (range, 1.8-3.1) LogMAR before the surgery. Despite conservative treatment, tectonic penetrating keratoplasty had to be performed in all patients in order to manage the perforation. Mean time in between initial examination and surgery was 10.75±12.04 (1-41) days. In 2 patients, allogenic limbal stem cell transplantation; in one patient, lateral tarsorrhaphy and in one patient symblepharon release with amniotic membrane transplantation were performed additional to tectonic keratoplasty. Mean follow-up time was 57.88±55.47 (4-141) weeks. Grafts were clear in 6 eyes and opaque in 5 eyes. The main causes of graft failure among opaque grafts were ocular surface disease (3), allograft rejection (1) and glaucoma-related endothelial failure (1). Phthisis bulbi was detected in one patient with congenital glaucoma due to vitreous loss at the time of perforation. The mean final VA in patients who had clear grafts was 1.83±1.03 (range, 0.8-3.1) LogMAR.

Conclusion:

To prevent serious complications in non-traumatic, non-infectious corneal perforations, providing anatomic integrity immediately is a must. If conservative treatment is inadequate or the perforation area is extensive, tectonic penetrating keratoplasty is indicated. Besides, it is important to manage the etiological risk factors in order to obtain successful clinical follow up.

1. INTRODUCTION

Corneal perforation is a severe corneal emergency that can occur due to traumatic or non-traumatic (infectious/non-infectious) causes [1]. There are serious complications such as cataract formation, glaucoma development, endophthalmitis, and globe loss due to corneal perforation and clinicians should be aware of these devastating complications. Restoration of the ocular integrity is the main goal of the management of non-traumatic, non-infectious corneal perforations.

Conservative treatments such as bandage contact lenses and pressure patching can be used to tamponade the leak. If conservative approaches are inefficient, surgical treatments such as multilayered amniotic membrane transplantation, conjunctival flaps and tectonic penetrating keratoplasty can be performed [2]. The preferred treatment modality is mostly based on size and the location of the perforation site. Large and central perforations generally require tectonic penetrating keratoplasty. However, emergency keratoplasty has a higher level of graft deficiency risk in comparison to elective keratoplasty and the postoperative Visual Acuity (VA) is lower in cases with corneal perforation after emergency keratoplasty [3-5].

The aim of this study is to report the clinical results of tectonic keratoplasty for non-traumatic, non-infectious corneal perforations.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

The medical records of twelve patients who underwent tectonic keratoplasty for non-traumatic, non-infectious corneal perforations between October 2014 and August 2018 at Ege University, Ophthalmology Department were retrospectively reviewed. The study protocol complied with the Declaration of Helsinki was approved by the Ege University, Faculty of Medicine Ethics Committee.

Data obtained from the records were evaluated for each of the following criteria: demographic characteristics, VA, cause, size and location of the perforation, surgical intervention types, complications and graft outcomes.

3. RESULTS

The mean age of the patients was 52.92±30.34 (range, 2-82) years. Male/female ratio was 5/7. The mean follow-up time was 57.88±55.47 (4-141) weeks. The cause of corneal perforation was a dry eye in nine patients. The causes of dry eye were neurotrophic keratopathy (n=4), limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD) (n=2), exposure keratopathy (n=2), and graft versus host disease (n=1). In the remaining three patients, the etiology of perforation was not determined.

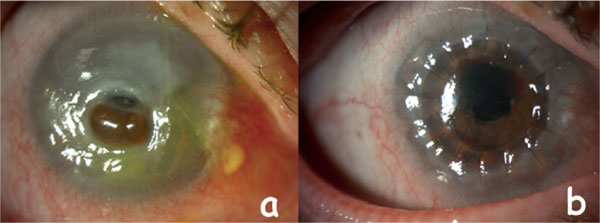

The initial mean VA was 2.98±0.39 (range, 1.8-3.1) LogMAR. Perforations were central in 8 eyes (Fig. 1a) and paracentral in 4 eyes. Iris prolapse from the perforation area was detected in 2 eyes. Conservative treatment was applied to all patients (bandage contact lens in two eyes and pressure patching in 10 eyes) before the tectonic keratoplasty surgery. The mean time between the presentation of the patients and the surgery was 10.75±12.04 (1-41) days.

There were additional surgeries in four patients, which were carried out at the same time with the keratoplasty. Living related limbal allograft transplantation was performed in two patients. Lateral tarsorrhaphy was performed in one patient and amniotic membrane transplantation was performed in one patient. Penetrating keratoplasty with interrupted 10-0 monofilament nylon sutures was performed in all patients. In 9 eyes, 7.5-7.75 mm; in 3 eyes, 8.00-8.25 mm vacuum-punch trephines were used. None of the cases had any intraoperative complications. All patients received topical antibiotics, steroids, cyclosporine 0.05% and artificial teardrops postoperatively.

Anatomic integrity was obtained in all eyes after tectonic keratoplasty. (Fig 1b) Phthisis bulbi evolved one month after the surgery in one patient with congenital glaucoma due to vitreous loss at the time of perforation. The grafts were clear in 6 of 11 eyes. The mean final VA in patients with clear grafts improved to 1.83±1.03 (range, 0.8-3.1) LogMAR. Even though grafts were clear, accompanying pathologies (1 vitreoretinal surgery history, 2 macular atrophy, 1 dense cataract) were the causes of limited VA. Graft failure was detected in 5 of 11 eyes. The causes of opaque grafts were; ocular surface diseases in three patients (neurotrophic keratopathy (n=1), persistent epithelial defect (n=1), LSCD (n=1)), allograft rejection in one patient and glaucoma-related endothelial failure in one patient.

4. DISCUSSION

Corneal disorders such as neurotrophic keratopathy, LSCD and exposure keratopathy can present with severe dry eye, which might lead to corneal melting and perforation [6-8]. The urgent management of perforation has a critical role in ensuring ocular integrity. Although elective keratoplasty mainly aims to improve VA, restoring the integrity of the globe is the principal goal of tectonic keratoplasty in patients with non-traumatic, non-infectious corneal perforations [9].

The most common causes of non-traumatic, non-infectious corneal perforations were reported as keratoconjunctivitis sicca [8] and neurotrophic ulcer [10]. In the present study, the most common etiological factor was a dry eye. The etiological factors related to the dry eye were neurotrophic keratopathy, LSCD, exposure keratopathy and graft versus host disease. There was no dry eye patient associated with the rheumatological disease, which is inconsistent with the literature. The reason for this inconsistency might be the application of strict treatment modalities and close follow up protocols for rheumatology patients in our hospital.

Corneal perforation localizations may be central, paracentral or peripheral. The localization of the perforation has an important role in the surgical treatment decision [2]. Although peripheral small-size corneal perforations might be treated with corneal patch grafting, in central corneal perforations, penetrating keratoplasty option should be preferred. In the present study, the most common location of the corneal perforation was central. In particular studies, it was demonstrated that solely central ulceration is a risk factor for perforation [11].

Conservative treatments such as bandage contact lens and pressure patching may stop leakage of aqueous humor and delay emergency surgery [10]. In the present study, despite the use of conservative approaches, there was a requirement for penetrating tectonic keratoplasty in order to provide ocular integrity in all patients. There are advantages of penetrating keratoplasty for restoring the ocular integrity in corneal perforations [12]. High rate of anatomical success was demonstrated throughout the literature [13-15]. In the present study, the anatomic integrity was obtained in all eyes, which is consistent with the literature. One month after the surgery, phthisis bulbi occurred in a patient with congenital glaucoma. The case was a two-year-old girl, and the cause of the eyeball loss was assumed to be the excessive amount of vitreous loss at the time of corneal perforation due to increased intraocular pressure because of crying.

As the main purpose of tectonic keratoplasty is providing the globe integrity, there would be some challenging issues with graft survival due to this emergency situation. The graft survival rate of the emergency keratoplasty was reported to be lower than the rate of elective ones [9, 16]. Sloan et al. [17] reported the graft clarity as 20% in patients with non-infectious corneal perforations. Lekskul et al. [18]achieved a clear graft in only 50% of the non-traumatic corneal perforation patients. In the present study, although the underlying pathologies were managed in order to obtain optimum graft survival, the graft transparency rate was 54.6%.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, it is important to stop leakage of aqueous humor as soon as possible in non-traumatic, non-infectious corneal perforations. If conservative approaches are not sufficient or a large perforation exists, penetrating keratoplasty should be performed. Management of etiological factors that lead to non-traumatic, non-infectious corneal perforations is also crucial.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The study protocol complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ege University, Faculty of Medicine Ethics Committee. (Approval number: 10-10.1T/40).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

Not applicable.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

Not applicable.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.