All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Late Onset Retinoblastoma Presenting with Vitreous Haemorrhage

Abstract

Our work describes the management of young patients who presents with vitreous haemorrhage. It is important to note that the causes differ significantly from adults with vitreous haemorrhage.

A 16-year old patient presented with vitreous haemorrhage. B-scan ultrasonography showed hypodense elements in the retina. A vascularized gelatinous mass was revealed after vitrectomy. Later the patient developed white cysts in the anterior chamber and histological findings were indicative of a retinoblastoma. The patient was enucleated and the diagnosis of retinoblastoma was confirmed. Intraocular surgery in young people with unknown retinoblastoma enhances the risk of metastasis development, orbital recurrence and death. Unexplained vitreous haemorrhage can obscure the view of a tumour but ultrasonic findings of a retinal mass calls for further imaging e.g. through MRI. The case illustrates the importance of excluding intraocular malignancy and advises a limited use of surgery in the initial examination of vitreous haemorrhage in young people.

INTRODUCTION

A 16-year-old girl presented with a one-week history of blurred vision of the left eye. She complained of one year of floaters in the same eye. Except a mild head trauma the previous year, past ocular and medical history was unremarkable and no ocular diseases were present in the family. Clinical examination of the left eye revealed a visual acuity of hand motion. Slit lamp examination demonstrated no abnormalities in the anterior segment. Fundus examination displayed vitreous haemorrhage, candle-wax spots and enlarged tortuous vessels. B-scan ultrasonography showed hypodense circular elements located peripherally in the inferior quadrants of the retina and no clear signs of retinal detachment. Intraocular pressure was 14 mmHg in both eyes. Visual acuity and examination of the right eye were normal. A vitrectomy was performed to visualize the retina and a vascularized gelatinous mass was revealed in the inferior temporal quadrant (Fig. 1A). The vitreous sample was cytological investigated. Fluorescein angiography showed numerous dilated vessels covering the lesion predominantly nourished from the retinal circulation and the lesion showed late hyper fluorescence Vitreous haemorrhage in young people is uncommon and trauma is the most frequent cause [1]. However, bleeding from proliferative retinopathies, infectious diseases, vascular abnormalities and tumours are additional causes (Table 1) [1,2].

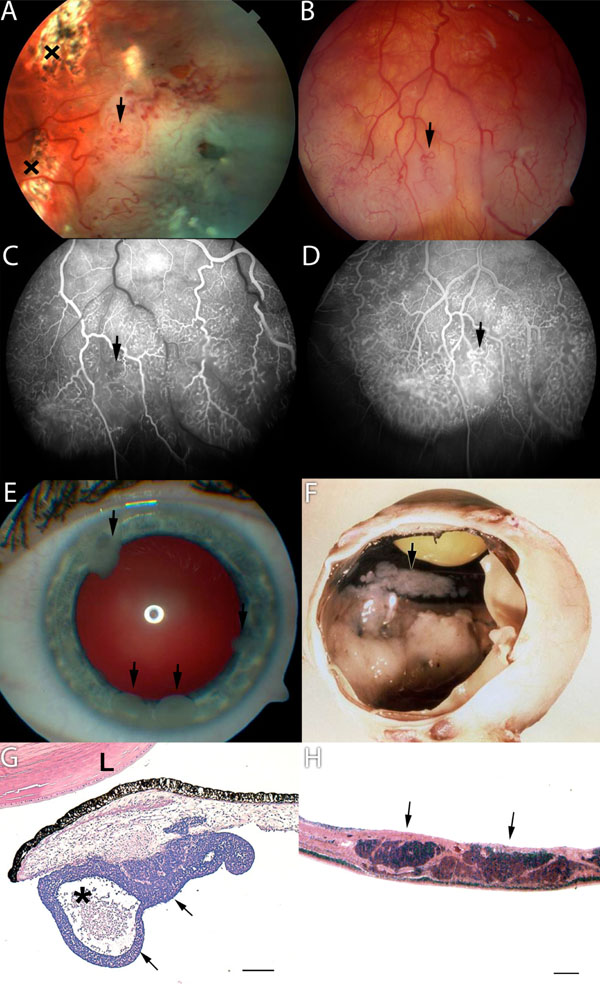

(A) An elevated retinal mass covered with dilated and tortuous vessels (arrow) was observed after vitrectomy and laser coagulation (x). (B) Five months later fundus photograph, (C) early and (D) late-phase fluorescein angiograms showed numerous abnormal intraretinal vessels in the progressed tumor mass. Note the limited diffuse leakage in the late phase fluorescein angiogram (D). (E) Seeding of the tumour with white lumps adherent to the front of the iris (arrows). (F) Macroscopical appearance with white tumour masses extending from the ora serrata to the posterior pole. Multifocal greyish tumour seeding was covering the back of the iris and the pars planitis corpus ciliare (arrow). (G) Micrograph of tumour satellite on anterior iris surface (arrows). The lesion has a cystic appearance because of the central necrotic space (asterisk). L = lens, hematoxylin and eosin stain, bar 500 µm. (H) Micrograph of retina with intraretinal tumour infiltration. Note the nearly complete lack of endo- and exophytic tumour growth. Hematoxylin and eosin stain, bar 100 µm.

Causes to Vitreous Haemorrhage in Young People

| Location of Abnormal Retinal Vessels | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| No Abnormal New Vessels | Extra Retinal Vessels | Intra Retinal Vessels | |

|

|

|||

| No Retinal Mass/Thickening | Ocular trauma | Regressed retinopathy of prematurity | Retinal vascular malformations |

| Tersons syndrome | Sickle cell retinopathy | Atriovenous communications | |

| Coagulopathy | Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy | Retinal macroaneurism | |

| Trombocytophenia | Diabetic retinopathy | ||

| Tromobophili | Retinal vein occlusion | ||

| Vitreous detachment( with or without retinal tear) | Retinal artery occlusion | ||

| X-linked juvenile retinoschisis | Retinal vasculitis | ||

| Pseudotumor cerebri | Ocular histoplasmosis | ||

| Ideopathic | |||

| Valsalva retinopathy | |||

|

|

|||

| Retinal Mass/Thickening | Bechet’s disease | Retinoblastoma | |

| Multiple sclerosis | Cavernous haemangioma | ||

| Syphilitic retinitis | Schwanoma | ||

| Dermatomyositis | Neurofibromatosis | ||

| Systemic lupus erythematousus | Retinal astrocytic hamartomaa | ||

| Sarcoidosis | Retinal Haemangiomab | ||

| Wegener’s granulomatousis | Vasoprolifreative tumours of the retina | ||

| Polyarteritis nodosa | Coats disease | ||

| Eales disease | |||

| Toxocariasis | |||

| Toxoplasmosis | |||

| Posterior uveitis | |||

| Acute lymphocytic Leukaemia | |||

| Lymphoma | |||

The differential diagnosis in this patient, who presented with a retinal vascularized mass in addition to vitreous haemorrhage, includes intraocular malignancy, benign vascular tumours and infectious or inflammatory diseases. Although infectious and inflammatory diseases can present with retinal infiltrates and ischemic induced neovascularization causing recurrent vitreous haemorrhage [3] these conditions were less likely in this patient. There was no perivascular sheathing, anterior inflammation or any systemic findings such as fever, skin lesions or tender lymphadenopathy. Additionally, the cellular response in the eye was noted to be predominantly erythrocytes and few neutrophils and large non-pigmented cells suspicious for malignancy. The material was too sparse for immunohistochemical staining, but a suspicion of a systemic disease was raised. A new biopsy was therefore not performed and the patient underwent an extensive hematologic work up, however Positron Emission Tomography – Computed Tomography (PET/CT), blood values and crista biopsy were all normal. The rich vascularity of the tumour and the lack of visible growth during the first two months suggested a benign vascular tumour. However, the exudation was limited and not as excessive as it could be expected for retinal haemangiomas or vasoproliferative tumours [4]. The disorder of the retinal vessels was also more distinct than generally observed in retinal vascular tumours. Retinal haemangioma occurs more commonly in individuals affected by von Hippel Lindaus disease [4]. However, in this patient genetic testing, urinary catecholamine levels, Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of brain and spine and abdominal ultrasonography were all normal. Despite five month of extensive systemic work no systemic disease could be detected and attention to the eye was re-established. Visual acuity had improved to 0,125 in the left eye, but slit lamp examination showed numerous white cysts in the anterior chamber adherent to the endothelium and the iris (Fig. 1E). Gonioscopy showed almost total occlusion of the chamber angle with white tumour masses and the left intraocular pressure had increased to 34 mmHg. Progression of the angiomatous tumour mass was observed by fundus examination and Fluorescein angiography (Fig. 1B-D). Histological findings from a transcorneal intralesionel biopsy of the anterior lesions were indicative of a retinoblastoma (Fig. 1G). Gross pathological examination after enucleation showed white tumour mass covering the ciliary body and seeding to the back of the iris (Fig. 1F). The diagnosis of retinoblastoma was confirmed by immunohistochemical findings (Fig. 1H).

This case was a diagnostic challenge as retinoblastoma rarely occurs in older children. The average age at diagnosis is 13 to 24 months and only 2% were older than 10 years in a review of 400 retinoblastoma patients [5]. The older patients showed a relatively lower survival rate due to several factors including extensive infiltrative tumour after delay in diagnosis and previous intraocular surgery [5]. Unexplained vitreous haemorrhage can obscure the view of a tumour but ultrasonic findings of a retinal mass without retinal detachment calls for further imaging e.g. through MRI. The risk of delaying appropriate treatment with a more conservative approach must be weighed against the risk of extra orbital seeding of malignant cells with intraocular surgery. Even though vitreous haemorrhage is a rare presenting sign of retinoblastoma the diagnosis was confirmed in 1,1 % of 168 patients under 18 years presenting with vitreous haemorrhage [1]. The use of vitrectomy in the primary management of vitreous bleeding in children should have the goal of preventing visual loss. In older children amblyopia is negliable and macula threatening rhegmatogenous retinal detachment can be ruled out by ultrasound. In all other cases with unexplained vitreous haemorrhage the diagnosis should be worked up before a vitrectomy is performed. Consultations with experienced retinoblastoma specialists are advised in any suspicious cases.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Declared none.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Declared none.