RESEARCH ARTICLE

Prevalence and Factors Associated with Active Trachoma among Children 1-9 years of Age in the Catchment Population of Tora Primary Hospital, Silte zone, Southern Ethiopia, 2020

Shemsu Kedir1, *, Kemal Lemnuro2, Mubarek Yesse1, Bahredin Abdella3, Mohammed Muze3, Abdulmejid Mustefa3, Mohammed Musema4, Leila Hussen1

Article Information

Identifiers and Pagination:

Year: 2021Volume: 15

First Page: 108

Last Page: 116

Publisher ID: TOOPHTJ-15-108

DOI: 10.2174/1874364102115010108

Article History:

Received Date: 23/12/2020Revision Received Date: 8/3/2021

Acceptance Date: 31/3/2021

Electronic publication date: 09/07/2021

Collection year: 2021

open-access license: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License (CC-BY 4.0), a copy of which is available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode. This license permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Background:

Trachoma is the foremost cause of wide-reaching, preventable blindness. According to the World Health Organization report, nearly 1.3 million human beings are sightless due to trachoma, whereas about eighty-four million are hurt from active trachoma. A survey revealed that the countrywide prevalence of active trachoma among children aged 1–9 years in Ethiopia was 40.1%. Limited data are present regarding the study area; therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the magnitude and factors associated with active trachoma among 1-9 years of children in the catchment population of Tora Primary Hospital, South Ethiopia.

Methods:

A community-based cross-sectional study was performed on 589 children in a study place from February 15 to March 13, 2020. We used Epi data program version 3.1 and SPSS version 20 for data entry and analysis, respectively.

Results:

The overall occurrence of active trachoma in the catchment was 29.4% [CI=25.7, 33.12]. Of these cases, the trachomatous follicle (TF) 90.9%, TI (4.8%), and combination of TF/TI (4.2%) were found. Households’ educational status, frequency of face washing, knowledge about trachoma, source of water for washing purposes, and garbage disposal system were the independently associated factors of active trachoma.

Conclusion:

In this study area, the occurrence of active trachoma was high. Hence, it needs instant attention, such as constructing a responsiveness application in the community, inspiring children and parents to try out face washing, improving knowledge about trachoma and appropriate excreta disposal.

1. INTRODUCTION

Trachoma is a contagious eye infection caused by the bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis. It is the prominent communicable cause of sightlessness globally [1-3]. The reservoir of contamination for active stages of the trachoma are children [4]. Persistent episodes of infection and the related conjunctival inflammation initiate a scarring process that eventually leads to irreparable blindness [5, 6]. The identification of active trachoma is a scientific diagnosis based on the WHO (World Health Organization) simplified categorizing system. The diagnosis of active trachoma are trachomatous inflammation – follicular (TF) and Trachomatous inflammation- Intense (TI). Both of them are mostly found in children but may occasionally occur in older persons. Each signal is graded as being absent or present. One or more symptoms can, and often do, manifest collectively [4, 7].

Trachoma is responsible for 1.4% of global blindness and an estimated annual productivity loss of up to US$8 billion. The number of people with moderate and severe visual impairment also increased, from 160 million in 1990 to 217 million in 2015 [8]. About 1.9 million people are blind or visually impaired due to trachoma [8]. According to 2017, the occurrence of TF in children aged 1–9 years was 165 million. 89% (146.3 million) out of 165 million people were in WHO’s African region and of which 69.8 million cases were from Ethiopia. 158 million people were living in districts in which the TF prevalence was greater than or equal to 5% by 17 April, 2018 [9]. Trachoma was recognized to be a public health problem in the 27 international locations of WHO’s Africa Region in 2016, and the absolute incidence of ailment are in sub-Saharan Africa, in particular in the Sahel belt and East Africa [10]. By 2016, more than 83 million people in Africa dealt with antibiotics for trachoma, which accounts for 97% of all antibiotic treatments for trachoma throughout the world [9].

Among SSA countries, Ethiopia ranks first in the list of the high burden on neglected tropical diseases in the 2010 WHO report [10]. Ethiopia, collectively with 4 other international locations, bears half of the international burden of active trachoma [11]. The national studies related to active trachoma conducted in Ethiopia (Trachomatous Inflammation- Follicular (TF) and Trachomatous Inflammation- Intense (TI)) for children 1-9 years old was 40.14%, and it is widely distributed in the country. Besides, the country-side assessment pointed out the highest prevalence in the Amhara region (62.6%), accompanied by the Oromia region (41.3%) [12].

The prevalence of active trachoma among children in the region of Southern nations, nationalities, and peoples’ region was 25.9%, and the highest prevalence was indicated from Amaro and Burji districts of Segen zone and Hadiya zone [13]. 75.4% and 36.5% of active trachoma cases were found in the Loma and Zala district of Ethiopia, respectively [14, 15].

Factors associated with active trachoma include the absence of solid waste disposal pit, latrine utilization, washing face by soap, frequent face washing, above five family size, the educational position of parents, wealth index status of the parents, knowledge status of parents head regarding trachoma, the distance of the latrine, density of flies on the face, and unclean faces [15-17].

The World Health Organization promotes the use of the SAFE strategy to prevent trachomatous blindness even though it is untreatable and surgery is needed for people who are at imminent risk of blindness. The Broad-spectrum drug, specifically Zithromax, is used to treat C. trachomatis infection and suppress the community transmission. Additionally, frequent face washing interrupts the transmission and reinfection of the disease, especially in children. The other cornerstone way of preventing trachomatous infection is behavioral change in environmental hygiene improvement [18].

Even though WHO plans to eliminate trachoma by 2020, active trachoma is still a concern of public health. The reason behind the selection of this catchment of the population is that more than 95% of the area has lowland agro ecologic features, and around only 50% has access to pipeline water. In addition to this, due to geographical location and sociodemographic factors, the risk factors of trachoma vary. Therefore, identifying the magnitude and the specific risk factor is critical to developing effective and tailored interventions. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the magnitude and factors associated with active trachoma among children in the study area.

2. METHODS AND MATERIALS

2.1. Study Setting and Design

A community-based cross-sectional study was employed among children aged 1–9 years in the catchment population of Tora primary hospital, Silte Zone, Southern Ethiopia, from February 15 to March 13, 2020. The catchment population of Tora primary hospital is located 178 km south of Addis Ababa and 159 km North of Hawassa. The catchment population of Tora primary hospital in almost all (around 95%) clusters has kola (low land area) agro-ecologic features except some areas in the Gebaba cluster, which has Wayne degas (Mid high land) areas. According to recent data from Silte Zone Health Department and respective woreda health offices, the catchment population was around 208,952 from Tora town administration, Lanfuro, Mitto, and East Silti Woredas in 2019. Of these, children aged 1-9 years were 68,915. There were thirty-seven (37) rural and four (4) urban Keble in the catchment. There was one primary governmental hospital, five health centers, and 41 health posts related to health infrastructure. Tora Primary Hospital catchment constitutes four (4) woreda, of which one is an urban town and administratively divided into 41 kebeles. There are 4 urban and 37 rural kebeles, and these kebeles are organized into six clusters based on nearest health facilities which include Tora, Repe, Gebaba, Mitto, Archuma wente, and Udassa clusters.

2.2. Sample Size Determination and Sampling Procedures

By considering the single population proportion formula, 36.7% of active trachoma, 10% non-response rate, and 1.5 design effect, the final sample size was 589 [15]. A multistage stratified sampling technique was applied to obtain study participants. We stratified the catchment into urban and rural with proportional allocation for the selected kebeles. Based on this, 13 were randomly selected (of which three of them were urban) out of 41 Kebele using Microsoft excel, and 4,362 households were present in these 13 selected kebeles. By using a systematic random sampling method, 589 households were selected, and with Kth value of every seventh household was identified for inclusion and visited one child per house was included in the study.

2.3. Data Collection Processes and Measurements

Data were collected by face-to-face interview, observation, and clinical eye examination by using a pretested interviewer-administered structured questionnaire. Different kinds of literature were reviewed to develop the questionnaire. For verifying consistency, the questionnaire was first prepared in English and translated to the local language Siltigna, and then translated back to English. Four integrated eye care workers (IECW) and two ophthalmic nurses were trained on the diagnosis of active trachoma by using binocular examination loupes lenses (× 2.5). Inspection of eyelashes, cornea, limbus, eversion of the upper lid, and inspection of the tarsal conjunctiva were examined carefully by considering the standard personal precautions. We used the WHO grading system for reporting eye examination results [2]. The dependent variable of this study was active trachoma status assessed by Trachomatous Follicle and Trachomatous Intense [2, 6].

2.4. Operational Definition

TF is diagnosed by the occurrence of five or more follicles of greater than 0.5mm in diameter in the central part of the upper tarsal conjunctiva [19].

TI is marked inflammatory thickening of the tarsal conjunctiva that obscures more than half of the normal deep tarsal vessels [19].

Clean face: If the face of a child is absent from an ocular or nasal discharge at the time of the visit.

Wealth index: First, all study participants were asked about the ownership of fixed assets by their household with a score of 1 given to those who owned the asset and a score of “0” given to those who did not own. Then principal component analysis was used to develop the wealth index and categorized into 3 tertiles [20].

Trachoma knowledge: After fifteen reliable trachoma knowledge questions were developed, we created their trachoma knowledge status and categorized into two components using principal component analysis (PCA). So, the first component HHs indicated those who scored “poor knowledge” and the last component HHs indicated those who scored “good knowledge”.

2.5. Data Quality Control

Two days of training was given for 6 data collectors and 2 supervisors for trachoma examiners (4 IECWs are tropical data certified trachoma graders, 2 diploma ophthalmic nurses as data collectors, and 2 BSc. optometrist as supervisors) before data collection. The questionnaire was also pre-tested on 5% of the final sample size in an adjacent Keble, which was out of the study area before the actual data collection. At each site, the data collectors were supervised intensively, and the completeness and accuracy of data were checked at the end of each day.

2.6. Statistical Data Analysis

The data were cleaned, and double-entry verification was employed in EpiData to ensure accuracy and completeness. Then, the data were entered into EPi-data version 3.1 and exported to SPSS version 20 for analysis. Frequencies, percentages, and summary statistics were done for descriptive findings. Variables with P-value < 0.2 in the binary logistic regression analysis were included in multivariable analysis to control confounding factors. The odds ratio at 95% CI was computed to show the strength of association between dependent and independent variables. The goodness of fitness of the model was assured by Hosmer and Lemeshow test (p=0.31), and the significance of associated variables were declared with P-value < 0.05 in the multivariable analysis.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Socio-demographic and Economic Characteristics

A total of 589 children aged l-9 years out of 561 children were visited for eye examination and made a response rate of 95.2%. The rest were not included due to refusal and incomplete data in the analysis. The majority of household heads, 415 (73.9%), were females with a mean age of 32 ± 6years. Most household heads, 515 (91.8%), were married. In addition to this, half of the households’ heads could not read and write, i.e., 303 (50.1%). 213 (37.9%) of households were in the category of low household assets (wealth index) (Table 1).

| Variables | Category | Trachoma status | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| House-hold sex | Female | 123(29.6%) | 292(70.4%) | 415(73.9%) |

| Male | 42(28.7%) | 104(71.3%) | 146(26.1%) | |

| House-hold parents age | 18-25 years | 10 (16.1%) | 52(83.9%) | 62(11%) |

| 26-35 years | 60(25%) | 180(75%) | 240(42.9%) | |

| 36-45 years | 65(34.5%) | 123(65.5%) | 188(33.5%) | |

| >=46 years | 30(42.3%) | 41(57.7%) | 71(12.6%) | |

| Educational status of parents | Read and write | 76(29.5%) | 182(70.5%) | 258(45.9%) |

| Not read and write | 89(29.3%) | 214(70.7%) | 303(54.1%) | |

| Place of residency | Urban | 36(21.7%) | 130(78.3%) | 166(29.6%) |

| Rural | 129(32.6%) | 266(67.4%) | 395(70.4%) | |

| Marital status of parents | Married | 149(28.9%) | 366(71.1%) | 515(91.8%) |

| Divorced & Widowed | 16(34.8%) | 30(65.2%) | 46(8.2%) | |

| Occupational status parents | Farmer | 124(32.5%) | 257(67.5%) | 381(67.9%) |

| Merchant | 31(25.2%) | 92(74.8%) | 123(21.9%) | |

| Govt employee | 5(18.5%) | 22(81.5%) | 27(4.9%) | |

| other | 5(16.7%) | 25(83.3%) | 30(5.3%) | |

| Number of persons per House hold | <=4 persons | 24(19.2%) | 101(80.8) | 125(22.3%) |

| >=5 persons | 141(32.3%) | 295(67.7%) | 436(77.7%) | |

| Wealth index (household assets) | Low | 71(33.3%) | 142(66.7) | 213(37.9%) |

| Medium | 56(27.6%) | 147(72.4%) | 203(36.2%) | |

| High | 38(26.2%) | 107(73.8%) | 145(25.9%) | |

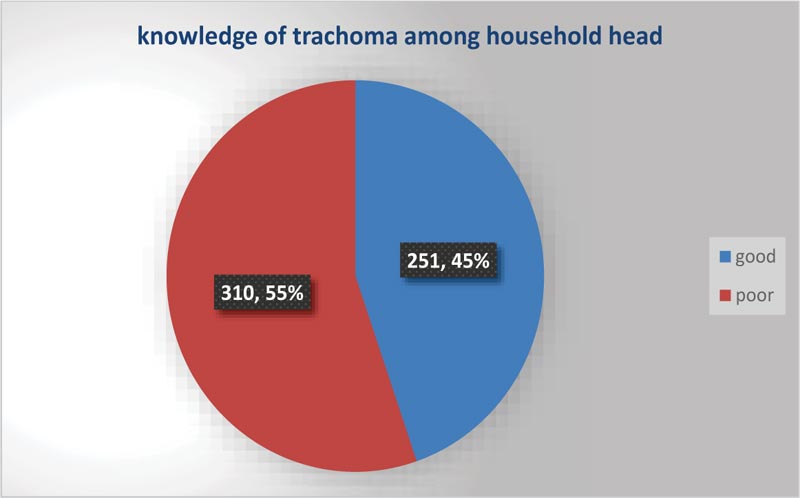

3.2. Knowledge about Trachoma Characteristic of Heads of Household

The reliability (Cronbach’s Alpha) of knowledge of trachoma-related factors was 0.87, and the household’s knowledge status about trachoma is shown below in Fig. (1).

3.3. Active Trachoma among Children of 1–9 Years Old

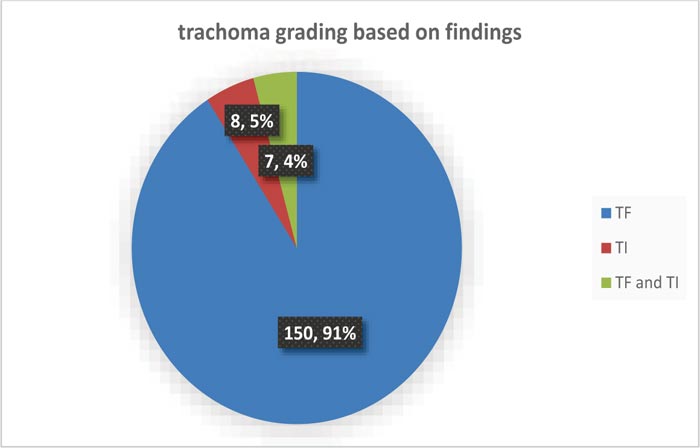

The overall prevalence of active trachoma was 165 (29.4%) with [CI=25.7, 33.12]. Of these, TF, TI, and a combination of TF and TI are mentioned in Fig. (2).

|

Fig. (1). Knowledge of trachoma among heads of household in the catchment population of Tora Primary Hospital from February 15 to March 13, 2020. |

|

Fig. (2). Active trachoma grading among 1-9 years of age in the catchment population of Tora Primary Hospital from February 15 to March 13, 2020. |

3.4. Environmental Related Factors

More than half of household’s source of drinking water, i.e., 317 (56.5%), was used pipeline water. Nearly 13% of households traveled more than 3 hours to get water. About 117 (31.6%) household’s cattle lived with the same household, and 223 (39.8%) of households had only one room. In most of the households, 325 (57.9%), flies were observed in the house, and the majority of them, 354 (63.1%), were bred in animal dung. Most households, 362 (59.2%), were cooked in detached places, and nearly all of them, 498 (88.7%) were out of windows (Table 2).

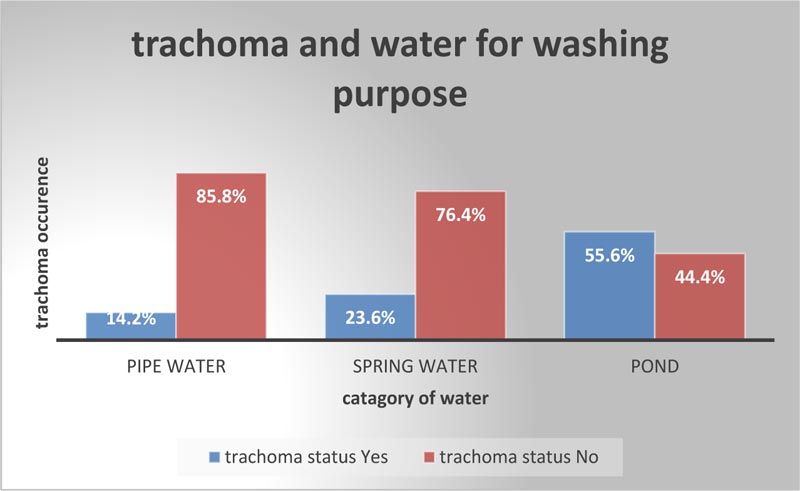

3.4.1. Trachoma and Water for Washing Purpose

Regarding water utilization for washing purposes, nearly half of the households developed trachoma due to pond water (Fig. 3).

|

Fig. (3). Active trachoma and water for washing purposes among 1-9 years of age in the catchment population of Tora Primary Hospital from February 15 to March 13, 2020. |

| Variables | Category | Trachoma status | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (%) | No (%) | |||

| Source of drink water | Pipe water | 105(33.1%) | 212(66.9%) | 317(56.5%) |

| Protected well spring | 20(20.2%) | 79(79.8%) | 99(17.6%) | |

| Unprotected spring | 14(18.9%) | 60(81.1%) | 74(13.2%) | |

| pond | 26(36.6%) | 45(63.4%) | 71(12.7%) | |

| Distance of water source | <30 minute | 30(12.4%) | 212(87.6%) | 242(43.1%) |

| 30-60 minute | 55(37.2%) | 93(62.8%) | 148(26.4%) | |

| 1-3 hours | 46(46%) | 54(54%) | 100(17.8%) | |

| >3 hours | 34(47.9%) | 37(52.3%) | 71(12.7%) | |

| Latrine availability | Yes | 99(22.1%) | 349(77.9%) | 448(79.8%) |

| No | 66(58.4%) | 47(41.6%) | 113(20.2%) | |

| Garbage disposal system | Yes | 33(15.7%) | 177(84.3%) | 210(37.4%) |

| No | 132(37.6%) | 219(62.4%) | 351(62.6%) | |

| Cattle living with the same household | No | 11(10.2%) | 97(89.8%) | 108(19.3%) |

| Living with same House hold | 86(48.6%) | 91(51.4%) | 117(31.6%) | |

| Live with same but separate house | 51(31.1%) | 113(68.9%) | 164(29.2%) | |

| Separate house | 17(15.2%) | 95(84.8%) | 112(19.9%) | |

| Number of rooms in the house | 1 room | 96(43%) | 127(57%) | 223(39.8%) |

| 2-3 room | 58(22.5%) | 200(77.5%) | 258(46%) | |

| >3 rooms | 11(13.8%) | 69(86.4%) | 80(14.2%) | |

| Flies observed in the compound | Yes | 131(40.3%) | 194(59.7%) | 325 (57.9%) |

| No | 30(12.7%) | 206(87.3%) | 236(42.1%) | |

| Flies breeding site | Animal dung | 104(29.4%) | 250(70.1%) | 354 (63.1%) |

| Human Faces | 3(10.3%) | 26(89.7%) | 29(5.1%) | |

| Liquid and solid waste | 58(32.6%) | 120(67.4%) | 178(31.7%) | |

| Cooking site | Same household | 89(44.7%) | 110(55.3%) | 199(40.8%) |

| Separate house hold | 76(20.9%) | 286(79.1%) | 362 (59.2% | |

| Cooking site with windows | Yes | 3(4.7%) | 57(95.3%) | 63(11.3%) |

| No | 162(98.1%) | 336(1.9%) | 498 (88.7%) | |

3.5. Child Related Factors

Half of the children, 282 (50.2%), were females in the mean age of 3 ± 1 years, and also 333 (59.4%) children were between the age of 3-6 years. The majority of children, i.e., 433 (77.2%), 385 (68.6%), and 288 (51.3%), had no ocular discharge, had clean faces, and washed their face more than once a day, respectively. The majority of children, 448 (79.8%), were preschool children, and 31 (5.6%) were not attending the school even if eligible. Most of the children, 450 (80.2%), did not wash their face with soap, and 193 (34.4%) children were observed with flies on their faces (Table 3).

3.6. Candidate and Significant Independent Variables Associated with Active Trachoma

Household socioeconomic factors like educational status, place of residency, and household assets (wealth index) were candidate variables. Regarding household environmental related factors, pond water for washing purposes, including face, latrine availability, flies observed in the compound, knowledge of trachoma, and any type of garbage disposal system were candidate variables for the outcome variable. In addition to this, frequent face washing and the sex of the child were candidate variables among child-related factors.

Finally, in multivariate binary logistic regression analysis, knowledge regarding trachoma, educational status of parents, pond water for washing purposes including face, frequency of face washing, and any type of garbage disposal system were independently associated factors for the study problem. Those children from households head having inadequate knowledge regarding trachoma were 4.3 times more likely to develop trachoma than those children from households headed by a person with adequate knowledge [AOR= 4.3 (95% CI= 2.6,7.3)]. Children from households with heads who could not read and write were 1.7 times more likely to develop trachoma than children from households with heads that could read and write. Children from households who used pond water for washing purposes, including face, were 3.5 times more likely to develop trachoma compared with the households that used pipeline water [AOR= 3.5(95% CI =1.9,6.5)]. Children from households who had no garbage disposal systems were 3.2 times more likely to develop trachoma than households who had garbage disposal systems [AOR= 3.2 (95%CI= 2,5.4)]. Moreover, children who washed their faces 2-3 per week were 7 times more likely to develop trachoma compared to those who washed their faces more than once per day [AOR= 7(95% CI =3.3,15] (Table 4).

| Variables | Category | Trachoma status | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Sex of child | Male | 95(34.1%) | 184(65.9%) | 279(49.7%) |

| Female | 70(24.8%) | 212(75.2%) | 282(50.2%) | |

| Age of child | 1-2 years | 28(24.3%) | 87(75.7%) | 115(20.5%) |

| 3-6 years | 120(36%) | 213(64%) | 333(59.4%) | |

| 7-9 years | 17(15%) | 96(85%) | 113(20.1%) | |

| Frequency of face washing | Once a day | 88(30.6%) | 200(69.4%) | 288(51.3%) |

| >once a day | 25(15.2%) | 140(84.8%) | 165(29.4%) | |

| 2-3/week | 52(48.1%) | 56(51.9%) | 108(19.3%) | |

| Ocular discharge | Yes | 46(35.9%) | 82(64.1%) | 128(22.8%) |

| No | 119(27.5%) | 314(72.5%) | 433(77.2%) | |

| Flies on their face | Yes | 76(39.4%) | 117(60.6%) | 193(34.4%) |

| No | 89(24.2%) | 279(75.8%) | 368(65.6%) | |

| Variables | Category | Trachoma status | COR (95%CI) | AOR (95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||

| Educational status of parents | Read and write | 76(29.5%) | 182(70.5%) | 1 | 1 |

| Not read and write | 89(29.3%) | 214(70.7%) | 1.59(1.1,2.3) | 1.7(1.01, 2.6)* | |

| Place of residency | Urban | 36(21.7%) | 130(78.3%) | 1 | 1 |

| Rural | 129(32.6%) | 266(67.4%) | 1.3(0.89,2) | 0.54(0.3,1.2) | |

| Wealth index (household assets) | Low | 71(33.3%) | 142(66.7) | 2.2(1.2,4.1) | 0.7(0.4,1.3) |

| Medium | 56(27.6%) | 147(72.4%) | 2.8(0.9,2.6) | 0.8(0.5,1.5) | |

| High | 38(26.2%) | 107(73.8%) | 1 | 1 | |

| Knowledge status trachoma among parents | poor | 129(41.6%) | 181(58.4%) | 4.2(2.8,6.5) | 4.3(2.6,7.3)* |

| good | 36(14.3%) | 215(85.7%) | 1 | 1 | |

| Source of water for washing | Pond water | 99(55.6%) | 79(44.4%) | 3(1.8,5) | 3.5(1.9,6.5)* |

| Spring water | 29(23.6%) | 94(76.4%) | 1.2(0.79,1.8) | 1.4(0.8,2.4) | |

| Pipe water | 37(14.2%) | 223(85.8%) | 1 | 1 | |

| Latrine availability | Yes | 99(22.1%) | 349(77.9%) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 66(58.4%) | 47(41.6%) | 4.9(3.2,7.6) | 2.9(0.99,5.8) | |

| Flies observed in the compound | Yes | 131(40.3%) | 194(59.7%) | 1.38(0.95,2) | 1.4(0.89,2.2) |

| No | 30(12.7%) | 206(87.3%) | 1 | 1 | |

| Sex of child | Male | 95(34.1%) | 184(65.9%) | 1 | 1 |

| Female | 70(24.8%) | 212(75.2%) | 1.5(1.1,2.3) | 1.5(0.97,2.4) | |

| Frequency of face washing | >Once a day | 25(15.2%) | 140(84.8%) | 1 | 1 |

| once a day | 88(30.6%) | 200(69.4%) | 2.1(1.3,3.3) | 1.6(0.95, 2.8) | |

| 2-3/week | 52(48.1%) | 56(51.9%) | 5.2(2.9,9.2) | 7(3.3,15)* | |

| Garbage disposal system | Yes | 33(15.7%) | 177(84.3%) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 132(37.6%) | 219(62.4%) | 3.2(2.1,4.9) | 3.2(2,5.4)* | |

4. DISCUSSION

The overall prevalence of active trachoma in this catchment was (165) 29.4%, [CI=25.7, 33.12] which includes trachomatous follicle (TF) (150) 90.9%, TI 8 (4.8%), and a combination of TF/TI 7 (4.2%). This result was almost comparable with studies conducted in Ethiopian national trachoma with a prevalence of 26.5% in the Tigray region and 33.2% in SNNPR [12], and 26.1% independent study in the Tigray region [21]. The occurrence of this study was once lower than reviews from Ethiopian country-wide trachoma prevalence in Oromo (62.6%) and Amhara (41.3%) [12], 64% in Southern Sudan [22], and 71% in Unity state in Southern Sudan [23]. This decrease in prevalence would possibly be the time of study season and different methodological differences. The prevalence was once greater than the study in Brazil, Senegal, Kanon state Nigeria [24], and Leku district in Sidema area [17], which account for 6.6%, 5%, 17.5%, and 11%, respectively. This might be related to the variation of the study period and the geographical and cultural factors of the district with poor infrastructure. The magnitude of this study was outside the WHO benchmark of public health concern [25-27] and contradicts the 2020 WHO elimination phase of trachoma.

In this study, children from family heads having insufficient knowledge about trachoma were 4.3 times more likely to develop trachoma than those children from households headed with enough knowledge of trachoma [AOR= 4.3(95% CI= 2.6,7.3). This is consistent with community-based studies carried out in the Basoliben district in Gojam [28], in the Gamagofa zone [15], and Tanzania [29]. This might be due to lesser access to information, training, and verbal exchange about trachoma in the district.

Children from households with heads who could not read and write were 1.7 times more likely to develop trachoma than the counterpart. Studies employed in Ethiopia were in concordance with these studies, and one of the associated variables of active trachoma was identified [17, 28, 30]. This is due to the fact that educational status restricts the care provided to children and hampers the utilization of health services. Likewise, the educational status of the family is also affected by availability, access to safe water, and basic sanitary facilities.

Children from households that used pond water for washing purposes, including faces were 3.5 times more likely to develop trachoma compared with the households that used pipeline water for washing purposes [AOR= 3.5(95% CI =1.9,6.5]. This study is in concordance with the study carried out in the North and South Wollo zone with findings showing a significant association between the source of water and the presence of active trachoma [31]. This finding was in line with the study conducted from Gazegibela district (north Ethiopia) [32]. This might be related to the quantity and/or quality of water to which the population has access since the interruption of water supply leads to inadequate storage [24, 33]. Furthermore, with a small amount of water available, hygiene actions are restricted. Studies conducted in the Gambia [34] and Ethiopia [31] reported a decrease in the transmission of C. trachomatis infection with better sanitation and water access.

Children from households who had no garbage disposal systems were 3.2 times more likely to develop trachoma than children from households who had garbage disposal systems [AOR= 3.2 (95%CI= 2,5.4)]. Studies conducted in the Gondar zuria district of Ethiopia [35] and Daworo zone of Ethiopia were in line with this study [14]. Disposing of wastes in the open field will end in favorable conditions for flies to breed and attract more vectors of trachoma, which might be a reason. Furthermore, children who washed their faces 2-3 times per week were 7 times more likely to develop trachoma compared to those that washed their faces more than once per day [AOR= 7(95% CI =3.3,15]. This variable is in concordance with studies conducted in Gondar zuria district [35], Gazegibela district [32] and Gonji Kolella district [36], and Wollo, Ethiopia [31]. The reason behind this might be that frequent face washing can interrupt the connection of children and flies.

5. LIMITATION

The drawback of this study is that it is subject to residual confounding when you consider that some manageable factors such as latrine distance, the distance of water source, and exceptional water issues were not properly addressed, and the effects may have been over or underestimated. In addition, the self-reported practices such as the reported use of soap by parents, the time when the face was last washed, and the frequency of face washing as reported by parents, may be uncertain due to social desirability bias. We attempted to decrease the blunders due to this by asking exclusive persons from households to answer the same question and considering the average value. We also explained the purpose of the study in detail.

CONCLUSION

The prevalence of this study was found to be high, and it is much greater than the WHO recommendation. Households’ educational status, frequent face washing, knowledge regarding trachoma, source of water for washing purposes, and garbage disposal system were the independently associated factors of active trachoma. Hence, it needs instant attention, such as constructing a responsiveness program regarding trachoma knowledge in the community, inspiring children and parents to run-through face washing, and appropriate excrete disposal systems. Intervention modalities that would address the identified associated factors are highly recommended to prevent and control active trachoma in this setting. The burden of active trachoma will reduce by the mass distribution of antibiotics by cooperating district health office and other relevant stakeholders. In addition, we should focus on availing enough water and sanitation facilities.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| AOR | = Adjusted Odds Ratio |

| CI | = Confidence Interval |

| COR | = Crud Odd Ratio |

| SAFE | = Surgery, Administration (drug), Face and Environment (clean) |

| SPSS | = Statistical Package for Social Sciences; |

| TF | = Trachomatous Follicles |

| TI | = Trachomatous Intense |

| WHO | = World Health Organization |

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Shemsu K designed the study, collected data, analyzed the data, and critically reviewed the manuscript. Kemal L, Mubarek Y, Mohammed M, Bahredin A, Abdulmejid M, Mohammed Muze, and Leila H designed the study, supervised data collection, analyzed the data, drafted the manuscript, and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Ethical approval was obtained from Werabe University Ethiopia Review committee. Ethical approval was given on 12/05/2020 with the number WRU/RPD/9/129/2020.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No Animals were used in this research. All human research procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national), and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

The study was conducted with a written consent that assures the willingness of each subject to participate in the study.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author [S.K] on reasonable request.

FUNDING

The research was conducted with financial funding from Werabe University under grant no. WRU1217.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge the Werabe University for their full collaboration and fund support during the study. Moreover, we would like to extend our deepest gratitude to all study participants and data collectors for their willingness and cooperation in this study.